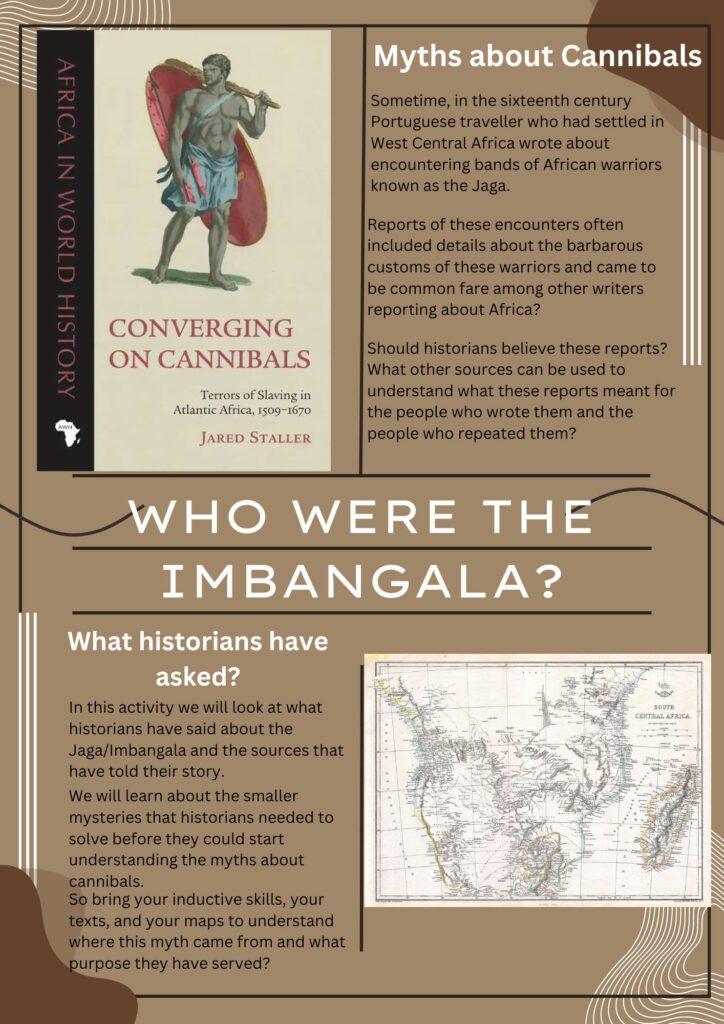

In the following assignment we will break down the main elements of Chapter 1: “An Introduction to Cannibal Talk” from the book Converging on Cannibals: Terrors of Slaving in Atlantic Africa 1509-1670 by Jared Staller (Ohio University Press, 2019).

The goal of this assignment is to practice how to identify the key elements of a secondary source. The activity is set-up to be completed as part of a Canvas course using the integration with the annotation tool “Hypothesis.”

This activity has two parts:

Part I.

- First, you will open the assignment called “An Introduction to Cannibal Talk”. You will be asked to open the assignment in a separate window.

When you open the secondary window, you will be in Hypothesis. Here you will be able to read the chapter and the annotations I have added to it. Pay close attention to the annotations I have added. They are there to introduce the elements of the chapter I want you to identify. In each annotation I identify one element, give you a brief explanation of it, and then assign a tag for it.

- I have annotated some of the initial pages, your assignment is to annotate the rest of the chapter. You will be asked to identify AT LEAST ONE EXAMPLE of each of the elements tagged in the reading. The elements you will have to identify and tag are:

- Story Chronology: Whenever you find a date or indication of WHEN something happened in the story told in the book.

- Story Characters: Whenever you find the name of a historical character.

- Story Places: Whenever you find a reference to a place or geographical marker such as mountains, rivers, etc.

- General Purpose: Any passage that helps you understand what is the general purpose of the author.

- Argument: Any passage that states, explains or elaborates on one of the arguments made in the book.

- Historiography: Any passage that explains or describes what other historians have said about the questions and arguments examined in the book.

- Primary Source: Any passage that describes the content of a primary source.

- Primary Source context: Any passage that describes and explains the context in which a primary source was created and/or preserved.

- Evidence: Any passage that explains the reasons why the author believes that his argument is correct. Evidence can come from the primary source, from secondary sources (for instance in the historiography), from specialists other than historians, etc.

- Significance: Any passage where the author talks about how his arguments or conclusions help us understand the present or the world beyond the narrow area of study in the book.

- To annotate select a passage that you want to annotate and click on the “Annotate” button. On the right side of your screen, you will find the text box to enter your annotation and a dropdown menu to enter your tag.

- In your annotation provide a brief explanation of why you chose that passage and why you decided to tag it in the way you did.

- The last dropdown menu will allow you to choose to publish your annotation to the whole class or just to yourself. Make sure you post it to all the class so I can see your annotations.

PART II

- In the second part of the assignment I want you to look at your annotations and those of your classmates and see if they help you better understand the chapter. Try answering the following questions:

- According to this chapter, the general purpose of the book is to correct some misconceptions. What are the misconceptions that this book seeks to correct?

- How would you articulate the main question this book is hoping to answer?

- How would you articulate the tentative answer he offers to his question? (This is what we can call the main argument).

- Have other historians asked the question investigated in this book?

- Which other historians have studied the history of the Imbangala?

- What is different about the questions asked by other historians and the questions asked in this book?

- Why did the author take a different approach to other historians in the past?

- How would you characterize this book in relation to the existing historiography? For example, does it prove that what other historians thought of the Imbangala was wrong? Does it build on the work that was previously done? What is the contribution that this book makes to the conversation about the history of the Imbangala?

- Answer these questions in a separate document and submit it by copying and pasting your answers in the text box.

Working on Hypothesis.

Now that you have seen the overall structure of the assignment. Let me show you what I have given students in terms of annotations.

I have added annotations and tags to identify key elements of the text. The purpose of this is to get them to slow down and develop the habit of reading the text in a more deliberate and active way, continuously asking themselves what is the purpose of a word or passage.

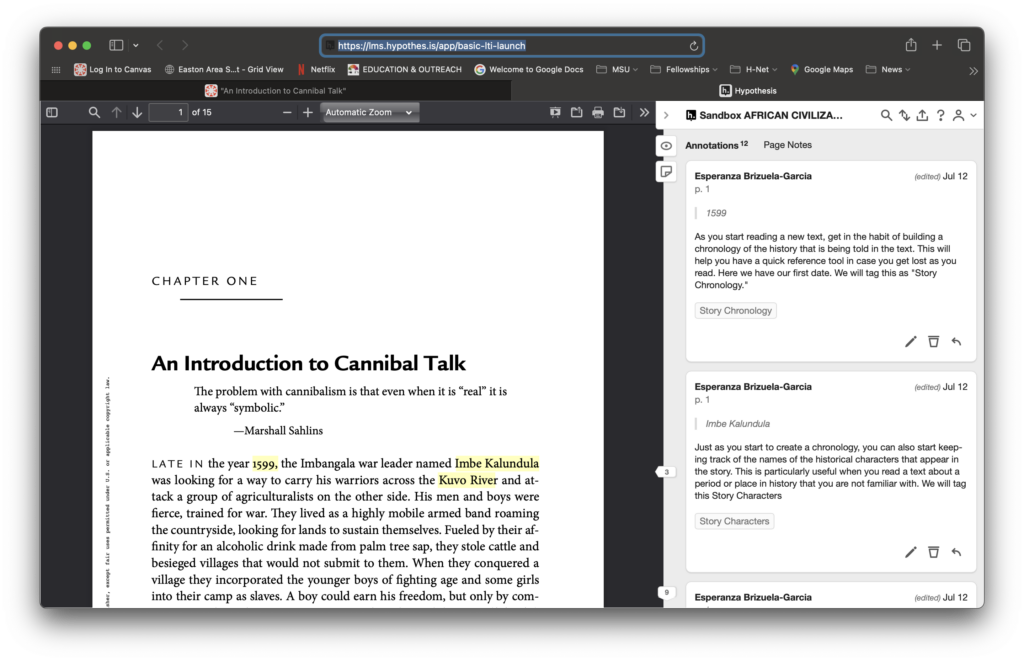

The first two annotations, for instance, are simply calling students’ attention to a date and a name. In both cases, I have added a tag for each of these. The purpose is for them to start getting in the habit of keeping track of names and dates as they read. In these two examples I introduced the tags “Story Chronology” and “Story character.”

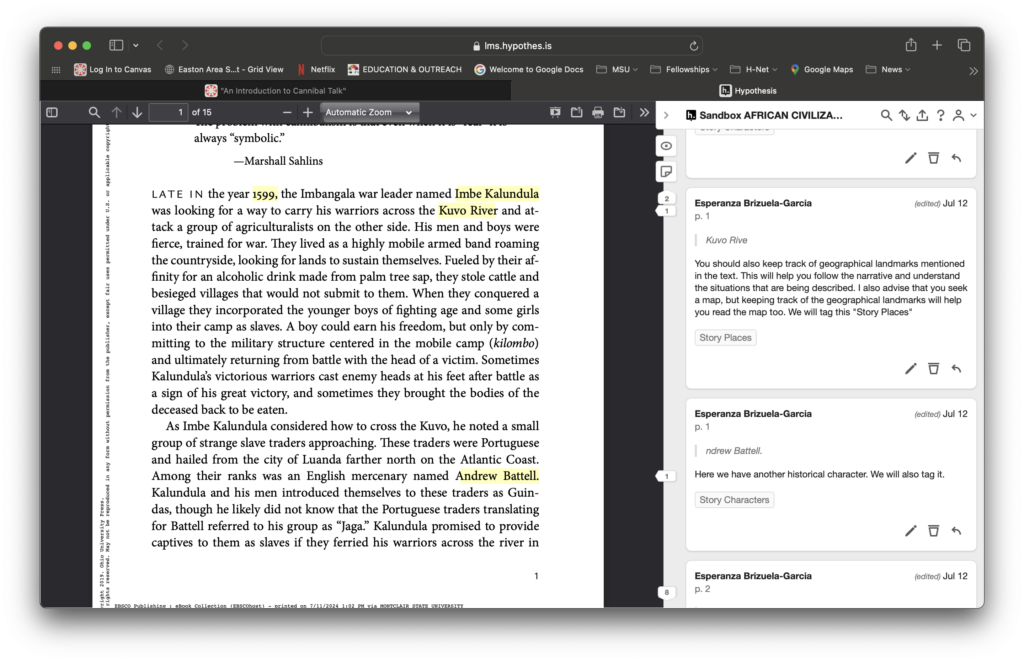

I also introduced tags for geographical references. As in the example below.

In addition to keeping track of elements of the story that is being told. I also want them to pay attention to instances when the author introduces or comments on the sources he is using. For these, I created two tags, “Primary Source” and “Primary Source Context”

Another important part of understanding that the stories they will be reading about are the result of long investigation into primary and secondary sources is to identify the historiography that allowed this research to exist.

Another important element that students tend to either ignore, or confuse with either the general purpose of the book, or the main argument, are the points that the author makes about the larger significance of their work. To help with this, I created a tag for “Significance.”

It is not always easy to articulate, in a few words, what the central argument or arguments of a book are. Sometimes, it is necessary to read carefully at the different points presented by the author, and often times too, the author repeats these throughout the text. Thus, it is important for students to know that they can find that central argument in various parts of the text and often, articulated in different ways.

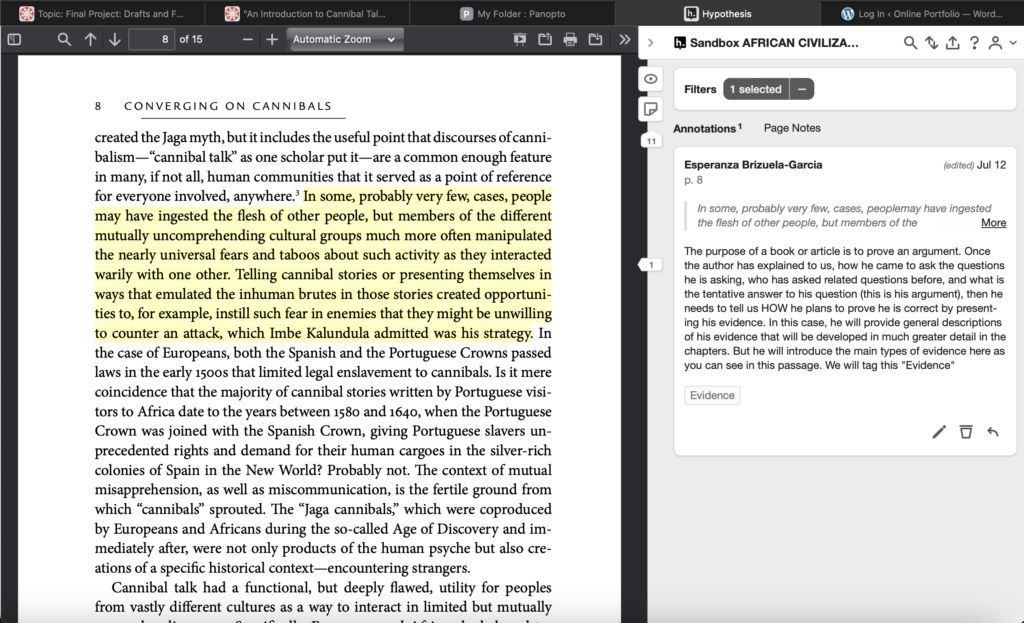

Finally, even in the introduction, authors start giving readers a some glimpses into the kind of evidence they will use in making their arguments. This is a good opportunity for students to be introduced to different kinds of evidence and see if this can prepare them to better follow and evaluate the arguments presented in the text. In the example below, I introduced a tag for “Evidence.”